Filmmakers and video artists engaged in the practice of appropriating, repurposing, and remixing video games are encouraged to send us their work for consideration. All submissions will be judged by an international panel of jurors comprising scholars, curators, and critics. A Critics' Award will be awarded to the most groundbreaking work.

BOOK: MACHINIMA VERNACOLARE

We’re happy to announce the release of volume one in the new series GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES edited by Matteo Bittanti: Machinima vernacolare by Riccardo Retez.

Available both on Amazon and Blurb in Italian, Machinima vernacolare examines the relationship between cinema, television, and video games, focusing on fandom productions that made machinima into a recognizable expression of popular culture and one of the most popular examples of user generated content.

Retez focuses on Grand Theft Auto V’s Rockstar Editor, a popular video editing tool used to created countless machinima. The author describes the production, consumption and distribution practices within an increasingly complex media environments. The analysis, which is accompanied by six case studies, demonstrates that far from being passive users, video game players can become guerrilla video makers.

Born and raised in Florence, Riccardo Retez received a Master's Degree in Television, Cinema and New Media from the IULM University of Milan in 2019 and a Degree in Graphic Design and Multimedia from the Free Academy of Fine Arts in Florence in 2017, where he studied the relationship between technology-based art practices culture and the humanities. Passionate about cinema, video games and visual culture, in the past five years Riccardo produced, edited, and directed several short films and video clips. Machinima vernacolare is his first book.

GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES examines the complex interaction between digital gaming and the visual arts through academic contributions situated at the intersection of different disciplinary areas – game studies, art criticism, visual studies, media studies and cultural studies – and gives voice to a new generation of researchers as well as established scholars. Both a critical and creative laboratory, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES promotes open dialogue, constructive debate, and sometimes idiosyncratic investigations of ideas, practices, and artefacts that – by their very nature – occupy different layers of today’s visual culture. Using a comparative rather than specialized approach, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES probes the most diverse visual experiences inspired by digital gaming.

To learn more about Machinima vernacolare, please visit this page, which includes a video walkthrough (in Italian).

To learn more about GAME VIDEO/ART STUDIES, please click here.

Siamo felici di annunciare la pubblicazione del primo volume della nuova collana GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES diretta da Matteo Bittanti: Machinima vernacolare di Riccardo Retez.

Disponibile su Amazon e Blurb in lingua italiana, Machinima vernacolare esamina il rapporto tra cinema, televisione e videogiochi e le dinamiche del fandom videoludico che ha elevato il machinima a una marca di riconoscimento delle produzioni user generated.

Retez esamina il Rockstar Editor, il software di montaggio video integrato a Grand Theft Auto V (2013),. L’autore descrive le dinamiche di produzione, consumo e distribuzione del machinima all’interno di un ecosistema mediale sempre più complesso. L’analisi, impreziosita da sei studi di caso, attesta che gli utenti di videogiochi non sono consumatori passivi di testi audiovisivi, bensì soggetti attivi in grado di comprendere e manipolare i significati variabili codificati in tali testi, proponendo sofisticati remake.

Nato e cresciuto a Firenze, Riccardo Retez ha conseguito una Laurea Magistrale in Televisione, cinema e nuovi media presso l’Università IULM di Milano nel 2019 e una Laurea in Graphic Design e Multimedia presso la Libera Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze nel 2017, dove ha studiato la relazione tra la cultura tecnico-artistica e tradizione umanistica. Appassionato di cinema, videogiochi e culture visive, Riccardo ha realizzato numerosi cortometraggi e videoclip. Machinima vernacolare è il suo primo libro.

Laboratorio critico e creativo, la collana GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES promuove un dialogo aperto, un confronto costruttivo e una disamina non necessariamente ortodossa di temi, pratiche e fenomeni che, per loro natura, s’intersecano con differenti livelli della cultura visiva. Privilegiando un approccio comparativo anziché specialistico, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES scandaglia le più diverse esperienze mediali ispirate dal e al videogioco per dare voce a una nuova generazione di ricercatori così come a studiosi consolidati.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Machinima vernacolare, visitate la pagina del libro, che contiene contenuti extra, tra cui una video presentazione dell’autore.

Per ulteriori informazioni su GAME VIDEO/ART STUDIES, cliccate qui.

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020 GOES FULLY DIGITAL

We are happy to announce that the 2020 edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL - which was postponed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic - will indeed take place. And sooner than later.

From Monday 25 till Saturday May 30 2020, the entire program will be fully available on the Festival website. This year, the work of 25 artists from 13 countries will be presented in 6 sections: GAME VIDEO ESSAY A, GAME VIDEO ESSAY B, THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, AND THE UNREAL plus three special programs (IN FOCUS).

The MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is part of the revamped Milano Digital Week 2020.

Click here to read the full program

SIAMO FELICI DI ANNUNCIARE CHE L’EDIZIONE 2020 DEL MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL PRECEDENTEMENTE POSTICIPATA PER VIA DELLA PERDURANTE PANDEMIA COVID-19, SI SVOLGERÀ ANCHE QUEST’ANNO.

Da lunedì 25 a sabato 30 maggio, l’intero programma sarà infatti interamente disponibile sul sito del festival. Il programma dell’edizione 2020 include opere realizzate da 25 artisti provenienti da 13 nazioni suddivise in 6 sezioni: GAME VIDEO ESSAY A, GAME VIDEO ESSAY B, THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, AND THE UNREAL e tre approfondimenti (IN FOCUS).

Il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL è un evento ufficiale della Milano Digital Week.

Clicca qui per leggere il programma completo.

NEWS: INTRODUCING VRAL

We are happy to announce VRAL, a uniquely curated game video experience, available for free on the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL website offering screenings of machinima created by artists and filmmakers whose work lies at the intersection of video art, cinema, gaming, and other visual practices.

The program features exceptional machinima selected based on their cultural relevance, artistic achievement, and innovative style. Often presented only in the context of festivals, exhibitions, and surveys, these works best represent the variety, ingenuity, and creativity of game-based video practices. A space providing access to diverse and innovative voices, VRAL is an online-only supplement to the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL. Throughout the year, VRAL celebrates a new generation of digital filmmakers and artists engaging with video game-based technologies, aesthetics, and practices.

The project comprises exclusive interviews, image galleries, and an archive.

VRAL begins April 25 2020 with the world premiere of Rapid Transit: Preface by Victor Morales.

LINK: VRAL

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020 (MARCH 09-13 2020, MILAN, ITALY)

We are delighted to announce the full program of the 2020 MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL.

The event takes place between March 09-13 2020 at IULM University in two separate locations: the Contemporary Exhibition Hall and the Sala dei 146, both located in the IULM Open Space building. Both venues are open to the public, but we kindly encourage attendees to register for the screening on Friday March 13 2020 in the Sala dei 146 as seats are limited.

Please note that each day features a different program. The festival is bookended by two sections titled GAME VIDEO ESSAY A (March 09 2020) and B (March 13 2020), after a successful run in the 2019 event of the4 same title. From Tuesday until Thursday we will present an indepth look at four artists whose daring, groundbreaking, unclassifiable work has redefined the aesthetics of machinima: Larry Achiampong, David Blandy, Jacky Connolly, and Oscar Wagenmans in the context of the Contemporary Exhibition Hall.

The festival concludes on Friday March 13 with The Weird, The Eerie, and The Unreal, which includes a selection of the most impressive works submitted this year and evaluated by our international jurors. During the screening, we will announce the 2020 Critics’ Award.

SCHEDULE

Monday March 09 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY A

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Tuesday March 10 2020

FOCUS: SAVEME OH

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Wednesday March 11 2020

FOCUS: JACKY CONNOLLY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Thursday March 12 2020

FOCUS: LARRY ACHIAMPONG & DAVID BLANDY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Friday March 13 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY B

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Friday March 13 2020

THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, THE UNREAL

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

18:00 - 20:00 Please RSVP

Click here to read the full program

Siamo lieti di annunciare il programma completo del MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020.

L'evento si svolge dal 09 al 13 marzo 2020 presso l'Università IULM in due sedi separate: la Contemporary Exhibition Hall e la Sala dei 146, entrambe situate nell'edificio IULM Open Space. Le sedi sono aperte al pubblico, ma invitiamo i visitatori a registrarsi per la proiezione di venerdì 13 marzo 2020 nella Sala dei 146, poiché i posti sono limitati. Si prega di notare che ogni giorno è previsto un programma diverso. Il festival è incorniciato da GAME VIDEO ESSAY A (09 marzo 2020) e B (13 marzo 2020), dopo il successo dell'esperienza nel 2019.

Da martedì a giovedì presenteremo uno sguardo approfondito su quattro artisti il cui lavoro innovativo ha ridefinito l'estetica del machinima: Larry Achiampong, David Blandy, Jacky Connolly e Oscar Wagenmans nel contesto della Contemporary Exhibition Hall.

Il festival si conclude venerdì 13 marzo con The Weird, The Eerie e The Unreal, che comprende una selezione delle opere più significative presentate quest'anno e valutate dai nostri giurati internazionali. Durante la proiezione, verrà annunciato il Premio della Critica 2020.

CALENDARIO

Lunedì 09 marzo 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY A

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Martedì 10 marzo 2020

FOCUS: SAVEME OH

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Mercoledì 11 marzo 2020

FOCUS: JACKY CONNOLLY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Giovedì 11 marzo 2020

FOCUS: LARRY ACHIAMPONG & DAVID BLANDY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Venerdì 13 marzo 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY B

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Venerdì 13 marzo 2020

THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, THE UNREAL

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

18:00 - 20:00 Registrazione richiesta

Cliccate qui per leggere il programma completo

MEDIA: SIGHT & SOUND ON THE ART OF MACHINIMA

"Machinima – a portmanteau of machine and cinema – the process of using real-time computer graphics engines to create a cinematic production [...] has existed for as long as in-game recording has been possible." Matt Turner aka Lost Futures provides a historical and critical overview of machinima, a digital form of filmmaking that lies at the intersection of experimental cinema and video art that began with Miltos Manetas’ Miracle, for Sight & Sound magazine. A must read.

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL (MARCH 16 2018)

MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

The aesthetics and politics of video game cinema: IULM University hosts the first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL.

MILAN - On Friday March 16, 2018 from 6.00 p.m. in the Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE) IULM University will host the first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL, an official event of the Milano Digital Week 2018.

A follow-up to the 2016 exhibition GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY organized by IULM University, this retrospective features a selection of machinima produced by international artists. Situated at the intersection between video games, experimental cinema and video art, machinima is an audiovisual genre that defies easy categorizations. Artists appropriate and modify pre-existing video games to create visually idiosyncratic experiences.

The first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL features Tayla Blewitt-Gray (Australia), Alan Butler (Ireland), Jacky Connolly (United States), Thomas Hawranke (Germany), Jonathan Vinel (France), and Eduardo Tassi (Italy) among others. A surprise screening will be announced the day of the festival. By hijacking Grand Theft Auto, The Sims, and other titles, these filmmakers created digital shorts focusing on such themes as sexuality, politics, alienation, creativity, and violence.

Curated by Matteo Bittanti, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is presented by Laura Carrera and Gemma Fantacci, students of the Master of Arts in Game Design of IULM.

Sponsored by the City of Milan, Department of Digital Transformation and Public Services, the Milan Digital Week (March 15-18, 2018) celebrates the driving forces that are reshaping work, leisure, and learning. By highlighting the interplay behind production and consumption made possible by digital technology, MDW aims at connecting citizens, companies, institutions, universities, and research centers.

MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

March 16th 2018

From 6.00 p.m. to 7.30 p.m.

IULM Open Space (IULM 6)

Via Carlo Bo 7

20143, Milano

Free and open to the public, upon registration

milanmachinimafestival.org

Jean-Baptiste Wejman

JEAN-BAPTISTE WEJMAN: "VIDEO GAMES ARE RAW MATERIAL THAT ARTISTS CAN - AND SHOULD - EXPLOIT"

In this interview, French artist Jean-Baptiste Wejman explains why Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe's works are "game-like" and why simulations and fictions are deeply intertwined.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman is an artist living and working in Toulouse, France. He received a Master of Arts in Fine Arts at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Bourges in 2014. An amateur photographer in his teenage years, he decided to become an artist at the age of 17, after attending a solo show by Mircea Cantor at FRAC in Reims. Influenced by artists such as Ryan Gander, Philippe Parreno, Pierre Huyghe, Cory Arcangel, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and Wolfgang Tillmans, he is interested in developing new practices of art and thinks that lacking a definition of art is, in itself, the most powerful engine for conceptual aesthetic thinking. His work has been exhibited internationally, including 35h (2015), a group show in Champigny-Sur-Marne near Paris, The Graduals (2012) at Traffic Arts Center in Dubai, and 43/77 (2009) in Bourges.

Wejman's installation Concentration Before a Burnout Scene is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you briefly describe your education and upbringing?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: I was lucky enough to experience an ordinary childhood, like many other kids growing up in the Nineties in France. As a teenager, I never envisioned that one day I would become an artist. I spent the best years of my youth playing video games, riding my BMX bike, reading and collecting used books, and listening to as many audio cassettes as I could. When I was still young, I had the chance to try my hand at photography with an old camera. I discovered Art in school, between the age of 11 and 15. I have to express my gratitude to the French educational system: it made me realize that art was an exciting field, not a moribund, boring discipline. I chose to concentrate in Fine Arts during my high school years. Around that time, I visited my first exhibition of Contemporary Art and that event changed my life. I had the opportunity to take excellent courses in Art History and I developed my first projects. Today, I keep them hidden in a remote space of my parents's garage! Back then, I enrolled in several science-based courses, but my passion for art was too strong to resist. Luckily, I was accepted by L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts in Bourges. Those were intense times. This is when I began to focus on a set of artistic concerns and to fully develop my art practice. I was very interested in research: I began investigating the status of the image, the deep meaning of photography, what lies behind the surface. My interest was definitely conceptual. In school, I kept asking myself: "What is my role as an artist?", "What is the goal of making art, today?", "What's the point in creating yet another image in the Twenty-first century?", "What kind of exposure can an artist's project receive?" and many more questions like these. Meeting like-minded peers was essential. Students, teachers, assistants, fellow artists... The conversations were intense! L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts gave me the chance to immerse myself in a lively art milieu and to participate in engaging discussions, stimulating debates, and constructive critiques. Finally, in 2014 I received a Master of Arts with honors. Since then, I have been developing my artistic activity.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Reprise, reprise déprise, 2016

Matteo Bittanti: Why did you begin to incorporate video games in your practice? What do you find fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality? Or are you more interested about the online communities that blossom around digital games?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: These are all excellent questions. Why? Well, for a long time I thought that the boundaries separating Art from "everything else" were clear, rigid, and somehow inviolable. Universal laws, so to speak. However, as time went by, I was forced to rethink my assumptions and to question my own prejudices. I was influenced by several critics and thinkers. One is Paul Ardenne, who believes that art should always be contextualized. He says that we must abandon the notion that each artwork is an autonomous object, existing in a vacuum. Ditto for Hal Foster, whose emphasis on theatricality forces us to think about artistic situations as always spatially situated. Since the Nineties, these discussions have evolved considerably: they might have taken new forms, but they certainly have not ended. Initially, what fascinated me about the role of video games within the contemporary visualscape was the ongoing debate around their status as art. As you know, "Are video games art?" is a question that dominated the conversation in the late Nineties and early Zeroes. For several critics, video games are just commercial artifacts, the byproduct of a creative industry akin to Hollywood. Other believe that games are still in their infancy, and, as such they are "under underdeveloped": once artists and intellectuals start unpacking their true potential, they will evolve in unexpected ways, subverting the conventions and clichés of mainstream productions. I began incorporating games in my practice around 2011 when I recognized their cultural value. To me, they were raw material that could - and should - be exploited by artists. Today, it is obvious to me that digital games are just another way of making art. We are overwhelmed by a staggering production of fiction, images, and interactions. We now posses the technical means to navigate virtual spaces. In a sense, we made Leon Battista Alberti's dream finally happen. My generation grew up watching a world unfold not outside "windows" but on Windows, jumping from one tab to another, playing with all sorts of information, assuming different identities and characters. As an artist, I wanted to partake this conversation and to experiment with new media. When I incorporated games in my artistic practice, the process felt natural, almost automatic. Perhaps even necessary.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Une table modifiée pour une machine qui génère un monde qui génère un personnage qui génère un voyage, 2014

Matteo Bittanti: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for their users. How do you relates to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension throughout your work in general and specifically in Concentration Before a Burnout Scene?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: The complex relationship between reality and simulation? This is where all the traditional questions of art clash and collide! Making pictures, chasing mimesis, imitating the real... And this is the reason why video games are so exciting. They force us to confront, once again, the notion of realism. And yet, we must not forget that since the early days of game development, many designers rejected realism in toto, offering instead alternative, more abstract, oneiric experiences. They questioned the notion of aesthetics in art through an image-based form of production. I must also add that, to me, the concept of simulation is closer to the broader concept of fiction. Not only these two notions have strong ties, but they inform each other, they are mutually reinforcing. In my practice, fictions act as simulations. For example, my video Concentration Before A Burnout Scene can be read on several levels. Initially I chose GTA San Andreas because I was fascinated by the very idea of the open world. This is where simulation truly matters. I produced this video by recording my own experience - mediated by an avatar - within the game world. This project qualifies as a machinima. At the same time, I selected a specific context and time frame within the game to extract some elements and to perform a loop. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene depicts the game in a static moment. It is a false movement stuck in an infinite time loop. In short, I simulated play time. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene is not about the "real" game, changing, developing and transforming before our own eyes. It is, on the contrary, a dramatization which offers the viewer the chance to experience an alternative experience of time. A simulated time that produces a duration in the so-called real world.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Live Wire Introduction, 2014

Matteo Bittanti: Do you consider yourself a gamer? Do you play videogames? If so, what titles do you find intriguing and stimulating, both, as a gamer and as an artist?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: Yes, I am a gamer, but a rather casual one. I do not have time to play all the games that I want. For instance, I did play Fallout: New Vegas. Not assiduously, like a dedicated gamer, but occasionally, like someone who finds himself fascinated by something he previously dismissed as "trivial". Thanks to emulation, I discovered old Sega Megadrive and SNES games that I could not play growing up because I found gaming too time consuming. Back then, I was always too busy doing something else, like reading or listening to music. In a sense, I am recapturing a part of my youth through retrogaming... So what are the games that an artist may find interesting? Definitely Minecraft. This is such a creative title, one that uses the very idea of open world in the most sophisticated and empowering way. Another game that truly fascinated me is The Stanley Parable: it was such an incredible gaming experience. There is little action, almost no gameplay. Just a voice that speaks to us, opening us up to almost endless possibilities. This is a self reflexive game, a game that questions itself through the medium of the video game. Very meta indeed. It was such memorable experience! Another title that blew me away is Undertale. This game is a tour de force. Using very simple technical means, this game produces a perfect narrative, engaging the player like very few other titles. Undertale breaks, or rather smashes, the fourth wall. It reminds me of something that David Lynch might have dreamed. You meet these amazing strange characters, and yet the world seems quite consistent. It makes sense even when it should not. When people ask me if there are games that offer experiences comparable - if not superior - to those produced by the best books, films, or paintings, I usually mention these three...

Matteo Bittanti: How do video game aesthetics affect the overall impact of your work? What comes first when you are developing a new project, the concept or the medium?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: Game aesthetics are truly fascinating because they link the narrative component to the gameplay. They are inseparable. Take Super Mario Bros.. Considered in itself, its universe is completely incoherent. The world that Mario inhabits is just a pretest to play. I mean, what is the deal with a mustachioed plumber who must rescue a princess in a strange world populated by flying fish and turtles? Even as an interactive fairy tale, it makes little sense. It's the gameplay that justifies the narrative. It's the action that makes the scenario, so to speak. I like to analyze video games in the same way that I examine a traditional work of art. I must understand the creator's process to fully appreciate a game. Consistency is by far the most important aspect of a game. The player must understand the logic of the simulated world. It cannot be random. Even randomness must have some coherence! And that's my challenge as an artist. How can I create works and exhibitions that offer situations where the public can establish a relationship with what I present? Is my world "consistent"? I often think of Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno's works. They create game-like spaces, spaces filled with characters, objects, and situations. Their works come with links, attachments, and identification processes. The same elements are pervasive in video games. These aspects deeply influence my own work. When I develop a new project, the concept is often the starting point. I try to consider how the final aesthetic position will engage the viewer. So I established a methodology according to the situation to produce a coherent "gameplay/scenario" that can be translated in an exhibition as "wandering/narrative".

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the process behind the production of Concentration Before a Burnout Scene?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: As I mentioned before, I chose to work with GTA San Andreas because at the time it seemed like the best game simulating the real world, at an architectural, narrative, social, and spectacular level. In short, this is a game that contains several layers of meaning and contexts. Additionally, GTA San Andreas allows emergent gameplay. I was looking for a space within the game that evoked the look-and-feel of film. A place where I could shoot a movie like Bullitt. I navigated the spaces of this virtual metropolis for weeks, seeking the perfect spot and finally, I identified the ideal area, located between the suburbs, stuck between a residential and an industrial zone. So I placed the main character CJ here in a car I've chosen because it resembled the archetypical muscle car - a Dodge Charger or a Ford Mustang - that one encounters in these films. I set my camera to capture the perfect angle, using a panoramic POV. The décor of the city, the visual clichés of the American urban environment were all in place. Then I started to capture the gameplay. At this point, I was working on a computer and I could easily capture a video source. I caught several sequences of twenty minute intervals. The challenge then was to create a short loop. The requisite was that the smoke exhaust and the ambient light must appear "natural". I produced a first version in MPEG 2 format in 2011. But for this exhibition, TRAVELOGUE, I reworked the source file to produce another video in 1080p. I consider this a form of digital restoration. It was a long process which took weeks. Although it may not seem like at first glance, I chose to show a passage where the heat effect distorts the image. I think this visual effect can distort the sense of time. The title is an integral part of the work. It contains several possible readings. It is clearly descriptive: what we see is, indeed, a character waiting in his car, idling, the engine running. He may be preparing to leave and make a U-turn in the middle of the road. But it also describes the expectation of the viewer. Lastly, it forces the viewer to concentrate on image and such concentration has limitations. It's a game on the expectation played on the viewer. A pending action, a possible story, an endless wait.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Dismantled Data, 2016

BOB BICKNELL-KNIGHT: "EVERY DAY WE REPLICATE THE IDEA OF WHAT LIFE SHOULD BE LIKE"

In this interview, British artist Bob-Bicknell-Knight discusses the effects of simulation on everyday life and the illusion of control of digital media.

Bob Bicknell-Knight is a London-based artist working in moving image, installation, sculpture and other digital mediums. Surveillance, the internet and the consumer capitalist culture within today’s society are the main issues surrounding his work alongside an intense fascination in the various cultures associated with video games and online communities. He explores these themes using tools and technologies, which are relatable but not restricted to art.

His 2016 artwork Simulated Ignorance is included in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you briefly describe your education and upbringing?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: Until a few years ago I had lived solely in the English countryside, only recently moving to London to undertake a degree in Fine Art at Chelsea. I now find myself focusing on ideas surrounding internet surveillance and video game aesthetics/ideas. A lot of my formative years were spent going on walks and exploring virtual worlds, occasionally going to museums and art galleries when I had the chance.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Consumerist Dissonance, 2016

"This piece considers the utopian relationships and spaces that we encounter within video game worlds and the escapism that is sought out within computer games as well as the futility associated with the accumulation of consumerist products." (Bob Bicknell-Knight)

Matteo Bittanti: Why did you begin to incorporate video games in your practice? What do you find especially fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality? Or are you more interested about the online communities that blossom around games?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: I’ve always played and enjoyed video games and have only recently begun to create work about them, due mostly to Jon Rafman and his extensive use of video games and their aesthetics within his own practice. When I saw his work, it was the first time that I realised one could actually make something that was valued, interesting and cohesive with the aesthetic and medium of video games. A lot of the aspects of video games that you’ve mentioned I’m interested in, especially the idea of interactivity and the communities that are formed around certain games. In terms of interactivity, with other forms of media, one rarely has any choice over what happens or any control over the flow of the experience; these are the two unique qualities of video games that sets them apart from standard tv shows or films. Rejecting the passive experience of simply viewing something through a screen is incredibly important to me. This interest in interactivity is hinted at within the installation, Simulated Ignorance, with the presence of a game controller, suggesting a sense of control to the viewer.

The extensive relationships that are formed through various online games are also intriguing to me, just listening to the passion in people talking about a raid in World of Warcraft or talking about a friend they met through Guild Wars definitely hints at the future of how we will interact with one another on a daily basis. A game that combines both interactivity and an online community incredibly well is Cloud Chamber, with the main body of the experience being simply posting on a message board, hoping that your particular ‘theory’ gets up-voted by the community in order to progress to the next level of the game. That progress is dependent on the friends that you make within this online experience is slightly disturbing to me, yet again hinting at possibilities to come.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, An Undignified Failure, 2016

Matteo Bittanti: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for their users. How do you relate to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension through your work and especially Simulated Ignorance?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: At this point the differences between reality and simulation are becoming increasingly blurred in offline and online cultures. Like Jim Carrey in The Truman Show, we find ourselves replicating an idea of what life should be like on a daily basis, often this is subliminally enforced by various medias to cater to the consumer. On the other hand, however, people are becoming more and more detached from their online self, creating multiple personas to embody when browsing ‘Web 2.0’, not fully realising the implications of such acts of apparent transgression. In my installation work, Simulated Ignorance, I’m seeking to highlight the multiple choices one has by providing the illusion of choice that the viewer is presented with, both challenging and confusing their preconceptions of violence and free will in video games.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Fabricated Loss, 2016

"A work exploring the tedium of daily life, the relationship between humans and technology as well as the idea of community." (Bob Bicknell-Knight)

Matteo Bittanti: How do video game aesthetics affect the overall impact of your work? What comes first when developing a new project, the concept or the medium?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: I feel that art works using the aesthetics of video games sometimes cloud the overall concept, allowing the viewer to simply focus on the animation of a video piece rather than considering what it’s actually about, dismissing it as ‘just about video games’ and only observing the ‘first layer’ of the work. I also think that using video games themselves for art in things like machinima have previously been looked at with disdain in the art world because of their seemingly ‘easy’ creation. Obviously this isn’t the case. Fortunately, this attitude towards video game artwork is slowly becoming obsolete, with more people becoming interested in this type of artwork as the video game industry continues to grow and flourish. My work always begins with the concept. I never set out to make a video or a sculpture as this would restrict me to those specific mediums when creating the work. When thinking about this question, I think of Ryan Gander, an artist without a medium whose work always begins with an idea, who then finds the medium best fitting to the initial thought, rather than being constrained by a material or technique that he’s learned over a number of years.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the creative process behind the production of Simulated Ignorance?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: A lot of my work begins with extensive research via the internet, from reading online articles to watching YouTube videos. At the time of this particular work’s creation, I’d been looking into the misguided activist Jack Thompson, a figurehead in various campaigns to ban violent video games with the argument that teenagers use them as ‘murder simulators’ to rehearse their violent plans. I knew that I wanted to make a piece of work about the preconceptions that people have about video games from watching ill-informed news articles. It also transpired that during this bout of research I’d been playing Grand Theft Auto 5, simply exploring the world, and as my time with the game progressed I began to get bored of endlessly shooting at things and decided to do what most people do at some point when playing an iteration of the GTA series; simply drive around the virtual world as if it were real life, sticking to the ‘rules of the road’. After a while I realised that the action of driving around in GTA was relatable enough to both the ‘gamer’ and ‘non-gamer’ and could form the basis of an interesting connection between the ideas surrounding violent video games that I’d been exploring in my research, with a game world that was incredibly appropriate to the subject matter.

COLL.EO, Photo courtesy of COLL.EO

COLL.EO: "VIDEO GAMES ARE WEAPONS OF MASS DISTRACTION"

In this brief interview, COLL.EO, discuss their latest project, INTERVALLO, an update to a 1960s Italian TV show meant as a "warning sign" of things to come.

COLL.EO is a collaboration between Colleen Flaherty and Matteo Bittanti established in 2012. Active in both San Francisco and Milan, COLL.EO creates boldly unoriginal media artworks, uncreative mobile sculptures, and uniquely derivative conceptual pieces. COLL.EO's work has been exhibited in the United States, Canada, France, Cuba, Mexico, and Italy.

Their project INTERVALLO is currently featured in TRAVELOGUE.

The interview was produced by RANDOM PARTS, an artist run collective located in Oakland, California.

COLL.EO, Postcards from Italy, mixed media, 2016, colleo.org

Random Parts: INTERVALLO is the third in a series of projects developed with Forza Horizon II after The Fregoli Delusions and Postcards from Italy. Is INTERVALLO the last episode of a trilogy? Is your détournement of Microsoft's racing game now complete?

COLL.EO: No.

COLL.EO The Fregoli Delusions - Chapter V machinima, color, sound, 2016, 37' 16" colleo.org

RANDOM PARTS: According to your statement, INTERVALLO pays homage a TV program - or rather, interlude - titled Intervallo which is basically unknown outside of Italy. What was this televised interlude about, and why did you decide to appropriate its format and subvert its message with video game imagery?

COLL.EO: The original Intervallo was an interstitial show produced by Italy's national public broadcasting company, Radio Televisione Italiana (RAI), between the 1960s and 1970s. Its "official" function was to fill the gaps between scheduled programming or during unexpected interruptions of live broadcasting and missing satellite feeds. Intervallo was basically a photo slideshow accompanied by soothing classical music. So, what's so special about it? Well, the original Intervallo, shot in black and white, depicted flocks of sheep. You read that right: flocks of sheep. You don't need to read between the lines to figure out that the National Broadcaster was telling its audience that they were a bunch of sheep, that is, "Someone who mindlessly follows and emulates anything and everything in the name of fame/recognition. A waste of flesh and brain cells." (Urban Dictionary) A televised lullaby, Intervallo's real message was: "Viewers, you are a bunch of morons. Look at you, glued to the screen, happy to be brainwashed by demented advertising, idiotic talk shows, celebrity crap, and political propaganda." A decade later, Berlusconi used his media empire - and especially his television networks - to take full control of Italy, as Erik Gandini has cogently illustrated in his 2009 documentary Videocracy. In a sense, Intervallo was a warning sign of things to come that nobody read. We updated Intervallo using imagery from a contemporary racing game set in an idealized, "postcard Italy", promising pristine vistas, economic empowerment, and fame through motorized bliss. And players of Forza Horizon II dutifully oblige: they collect supercars, dream of endless material wealth in a world where air pollution, accidents, and peak oil do not seem to exist, and drive around without really going anywhere. Like TV, video games are weapons of mass distraction: they promise agency and autonomy, but all they produce, in reality, is acquiescent, passive users. And that's what makes them terribly interesting. Video games are meant to be exploited and subverted.

RANDOM PARTS: How did you find the screenshots of each slideshow?

COLL.EO: We collected the images by downloading them one by one from the online community hub of Forza Horizon II. We picked each image instead of downloading them in a batch, automatically. That was part of the process. As you can imagine, that took some time. We collected hundreds, if not thousands of screenshots, and then identified recurrent themes - e.g., glitches, bugs, ghosts, and so on. We edited them, adding the original soundtrack from RAI's Intervallo. There's a visual narrative unfolding in each of the four episodes we've released so far. It's up to the viewers to decode the meaning of each video. They can watch INTERVALLO while the game console loads the new game.

ISABELLE ARVERS: "MACHINIMA IS IDEAL FOR DÉTOURNEMENT"

la traduzione italiana è sotto

In this interview, excerpted from a longer conversation that will be featured in the TRAVELOGUE catalogue, art critic, curator, and machinimaker Isabelle Arvers explains why machinima is the ultimate form of détournement.

Isabelle Arvers will participate in a panel titled CRASH: GAME AESTHETICS AND CONTEMPORARY ART on Sunday September 11, 2016 at 11:30 with Valentina Tanni. Click here for more information. Click here to read an interview with Tanni.

Matteo Bittanti: How would you describe the difference between video games and game videos, that is, machinima and video works created with digital games to somebody who is unfamiliar with these cultural artifacts? And what do you find so fascinating about machinima, both aesthetically and conceptually?

Isabelle Arvers: The main difference is interactivity, which is not a feature of machinima, unless you create an interactive machinima experience through an installation or performance. In order to produce a machinima one must use video game technology and play a video game, but the outcome is a linear movie, film, or video. That final product - i.e. the video - can be used as raw material to create something else that could become interactive or not. Most of the times, machinima is non-interactive. So interactivity is a key factor. But there is more...

Once, during a machinima workshop, a student of mine told me something interesting. He said that the main difference between machinima and video games is that with a machinima you can always decide what would happen next, unlike video games where it is “always the same”. I asked what he meant and he said: "After you play the game several times, you know exactly what is going to happen, over and over, and you have almost no control. You just go through the motions, pressing the buttons at the right time". It sounded counterintuitive at first, but I think he was onto something profound. Basically, what he meant is: games are repetitive, machinima is creative.

Another difference lies in the artist's intentions. A gamer and an artist have very different agendas. Playing requires specific skills like coordination and responsiveness. But a gamer basically reacts to predefined inputs. An artist is a true creator, a producer, a so-called prosumer, that is, a producer-consumer. When you make a machinima, you play the role of the content producer: you can express an original idea and use different tools to communicate your message. In other words, you are very active when you produce a non-interactive film. You become a creator rather than a user. A user is a consumer of an “interactive” experience designed by someone else.

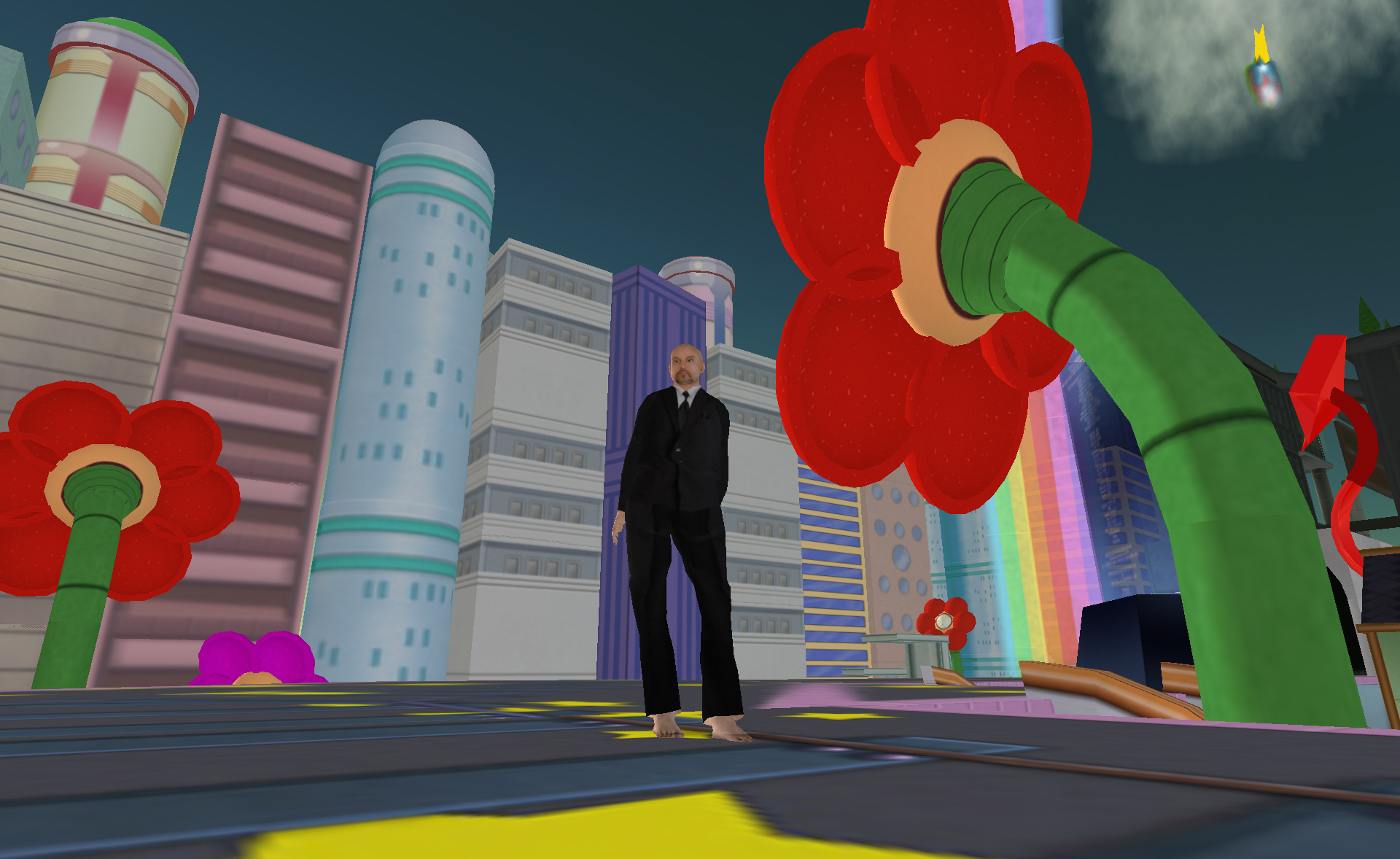

Douglas Gayeton, Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, 2007.

I think that this is the ultimate message of Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, Douglas Gayeton’s machinima documentary filmed in Second Life. In the film, the protagonist is searching for the creator of the virtual world. On his way to enlightenment, he meets several characters. Finally, he discovers that the creators is all of us. The sad part is that we do not get any Intellectual Property benefits from the work we produce: all the rights are owned by the game publishing companies.

In addition to the fact that machinima is a form of reverse-engineering of a video game - to make a machinima is to deconstruct a game and to reconstruct it in a different form - what fascinates me most is the idea of détournement. This situationist technique is about appropriating, reconfiguring, and subverting an existing artifact. To create a machinima is to do something unexpected, something that was not supposed to happen. It’s about transforming an object into something else. To make a machinima is to actively and creatively use a virtual space belonging to popular culture to express different ideas and to deliver an alternative message, because the creator is actively adding a new layer of content onto familiar images. The Situationists used to détourn movies because back in the Sixties cinema was a popular artform, and so, it was able to reach the masses. Today, video games have mass appeal and thus are an ideal medium for détournement.

Matteo Bittanti: Do you consider machinima a genre of video art? Or is it closer to fandom? As a practice, is it confined to game culture? It is separated and/or segregated from the artworld as a whole?

Isabelle Arvers: Machinima can stimulate our minds and deliver different kinds of messages. It enhances our perception and forces us to critically distance ourselves from commercial video and computer games. There is a long tradition of incorporating and using toys and games to make art. Machinima is simply the latest iteration of a process that was pioneered by avant-garde movements like DaDa and Surrealism. Both saw entertainment and play as the most subversive form of art. For them, play was a critical tool.

Video games and Surrealism share many affinities. Consider, for instance, the phenomenon of game dreaming, that is, the tendency of visualizing video game sequences or puzzles while asleep. It is obvious that games influence our mind, perhaps on a subconscious level. To make a machinima is to rearrange the world of a video game, the characters’ behavior, the scenery or the objects. The machinimaker changes the color of the sky, modifies the speed of the animation, or alters the game’s variables. Just like any other artform, machinima influences the way we look at reality. Consider Oscar Wilde’s famous essay, “The Decay Of Lying – An Observation”. All the ideas he discussed in that piece are still valid today. In short, I don’t think that machinima is just an expression of game culture. It is not separated from the artworld and certainly not segregated.

When machinima is not exhibited online or in film festivals but in the context of an art exhibition, it is presented most of the time as video art. But machinima is more like a technique than a genre in itself. Often, when visitors see machinima in an art space and they are unfamiliar with games, they cannot recognize the “source”, that is, games. All they see is three dimensional images. They see computer graphics. But that does not undermine the value of the piece and it certainly does not compromise the viewers' understanding. Additionally, because machinima is still considered a new genre after twenty years of existence, it keeps experimenting and borrowing from the language of film and from non-narrative video art. Today, very few artworks are so influenced by game aesthetics that they cannot be appreciated by an audience unfamiliar with the intricacies of the gaming vernacular. But I also believe that machinima needs to diversity itself and interact with different disciplines in order to become something else, something more, for example, a space that can be inhabited, rather than images on a screen.

Cross By. An immersive exhibition for piano and machinima, June 2016, Aix-en-Provence, France. Isabelle Arvers is responsible for the machinima component of the performance.

Matteo Bittanti: What role does machinima occupy in the current visual landscape? And how did it change overtime?

Isabelle Arvers: I find the evolution of machinima very interesting. Machinima emerged exactly two decades ago within the so-called "hard core" game scene. For several years, it only circulated online. Subsequently, it started to be featured in dedicated festivals and in special programs of major film retrospectives. After 2006, machinima transcended the game culture scene and became a recurrent presence both within the film sphere and the Artworld.

In 2011, I curated a survey show within a larger digital art exhibition and approximately 60% of the artists involved were not gamers at all, but called themselves "film directors". For them, machinima was simply an accessible, inexpensive way to make 3D movies and to express themselves in cinematic terms. In other words, they were making "digital movies". Meanwhile, machinima was mostly ignored by the artworld until 2010, but it became a thing with the rise of the post-internet movement that considered games as contemporary artifacts worthy of critical examination.

In the post-internet scenario, machinima began to inhabit the artworld: it was not an unwelcome guest any longer. It became a staple in biennales and exhibitions. A handful of art galleries now regularly represent artists who make machinima and artworks influenced by 3D graphics, computer animation, and the web. It all began with Miltos Manetas, but artists like Cory Arcangel, Jon Rafman, Larry Achiampong and David Blandy have really blurred the lines between games, machinima, and contemporary art. Interestingly, when machinima entered the artworld, it lost its political edge and became pure aesthetics. Nowadays, young artists use games images, websites or animation as a raw material to produce installations, paintings or video works.

I am happy to say that thanks to the machinima workshops I gave in both Fine Arts and Game Design schools in France, several students who never thought about using machinima to make art have incorporated this techniques in their work. This is particularly exciting because several different contexts - technology, art, cinema, gaming - are now talking to each other in novel ways. I think machinima has now become part of a broader visual landscape than the avant-garde or the so-called underground of the Nineties. Machinima is also related to mash-up culture because of its hybrid nature. It is a mix of collage and reappropriation—indeed the concept itself is a mashup, as it conflates cinema and video games. So, besides the post-internet movement, machinima now belongs to a wider visualscape that includes the DJ and the VJ scene, video clips, remix, and more. Machinima is part of a mix of disciplines, cultures, and practices that, hopefully, will give rise to interesting, not-yet-identified cultural objects.

ISABELLE ARVERS (b. 1972) is a French media art curator, critic and author, specializing in video and computer games, web animation, digital cinema, retrogaming, chiptune music, and machinima. She curated several exhibitions in France and internationally on the relationship between art, video games, and politics including the seminal Gizmoland the Video Cuts (Centre Pompidou, 2001), the Gaming Room at PLAYTIME(Villette Numérique, Paris, 2002), Tour of the Web (Centre Pompidou, 2003), featuring Vuk Cosic and Miltos Manetas among others, Digital Salon. Games and Cinema (Maison Populaire, Montreuil, 2011), GAME HEROES(Alcazar, Marseille, 2011) and several editions of GAMERZ (Aix-en-Provence, France). She also promotes free and open source culture as well as indie games and art games. A graduate of the Institute of Political Studies in Aix-en-Provence and a Postgraduate Diploma in Cultural Project Management of the Paris 8 University, Isabelle Arvers has been researching and working with new media since 1993. A prolific writer, her critical essays have been included in several catalogs, anthologies, and books. Arvers lives and works in Marseille.

Isabelle Arvers parteciperà all'incontro CRASH: ESTETICHE VIDEOLUDICHE E ARTE CONTEMPORANEA che si terrà domenica 11 settembre alle ore 11:30 insieme a Valentina Tanni. Cliccate qui per ulteriori informazioni. Clicca qui per leggere un'intervista con Tanni.

Matteo Bittanti: Come spiegheresti la differenza tra video giochi e giochi video, ossia machinima e altre produzioni audiovisive create con i video game, a chi non possiede grande dimestichezza con questi artefatti culturali? Inoltre, cosa ti affascina in particolare del machinima, sia a livello estetico che concettuale?

Isabelle Arvers: La differenza essenziale è l'interattività, che non è una caratteristica del machinima, a meno che un autore decida di produrre un machinima interattivo attraverso un'installazione o una performance. Anche se un creatore che vuole produrre un machinima deve usare la tecnologia del videogioco nonché "giocare" per effettuare delle riprese, il risultato è un'opera lineare, che si tratti di un filmato, di un corto o lungometraggio. Certo, il video risultante può essere usato come materiale grezzo per creare qualcos'altro, ma nella stragrande maggioranza dei casi, il machinima non è interattivo. Quindi l'interattività rappresenta un importante fattore discriminante. Ma c'è di più...

Una volta, durante un workshop machinima che avevo organizzato in una scuola parigina, un mio studente ha detto una cosa che mi ha colpito molto. Ha dichiarato che la differenza tra il machinima e il videogioco è che in un machinima è possibile "decidere quello che succederà dopo", mentre in un videogioco "è sempre la stessa cosa". Ho chiesto delucidazioni e mi ha risposto: "Dopo aver giocato a un videogioco diverse volte, sai esattamente cosa succederà, le cose si ripetono in modo sempre identico, il giocatore ha un controllo limitato. Si tratta semplicemente di ripetere una sequenza, di premere i pulsanti al momento giusto e poco altro." Anche se all'inizio può suonare bizzarro, le sue affermazioni rivelano una profonda comprensione del potenziale - ma anche dei limiti - del videogioco. In breve: mentre i videogiochi sono ripetitivi, il machinima è creativo.

Un altro importante fattore discriminante riguarda le intenzioni dell'artista. Un giocatore e un artista hanno obiettivi differenti. Il videogiocare richiede abilità particolari come la coordinazione occhio-mano e la capacità di rispondere rapidamente agli stimoli audiovisivi. Ma un giocatore riflette a sollecitazioni predefinite. Per converso, l'artista è un vero creatore, un produttore, un cosiddetto prosumer, contrazione di producer-consumer. Creando un machinima, interpretiamo il ruolo del produttore di contenuti: possiamo esprimere un'idea originale, usando differenti strumenti. In altre parole, siamo davvero "attivi" quando produciamo un film non-interattivo. Siamo "creatori" anzichè "utenti". Un utente è un consumatore di un'esperienza "interattiva" progettata da qualcun altro.

Douglas Gayeton, Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, 2007

Questo è il messaggio profondo di Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, il machinima doc del regista americano Douglas Gayeton girato in Second Life. Nel suo film, il protagonista è alla ricerca del creatore del mondo virtuale. Lungo il cammino, incontra numerosi personaggi. Alla fine, scopre che il creatore, in realtà, siamo noi. Sfortunatamente, non beneficiamo di alcun vantaggio economico: l'azienda che ha "prodotto" il gioco detiene tutti i diritti. Una beffa.

Oltre ad essere una forma di reverse-engineering di un videogioco - produrre un machinima significa decostruire un videogioco e ricostruirlo in forma differente - ciò che mi affascina di più del machinima è la nozione di détournement. Questa tecnica situazionista consiste nell'appropriarsi, riconfigurare e sovvertire un artefatto esistente. Creare un machinima significa fare qualcosa che non si dovrebbe fare: si tratta di trasformare un oggetto in qualcosa di differente. Produrre un machinima significa usare in modo attivo e creativo uno spazio virtuale che appartiene alla pop culture per esprimere idee alternative, differenti, dato che il creatore aggiunge dei significati assenti nell'opera originale. I Situazionisti utilizzavano la tecnica del détournement per il cinema perché si trattava di una forma popolare di intrattenimento e, come tale, era in grado di raggiungere le masse. Oggi sono i videogiochi ad avere un appeal popolare e per tanto sono il medium ideale per il détournement.

Matteo Bittanti: Consideri il machinima un genere di videoarte? Oppure è un'espressione del fandom videoludico? Si tratta di una pratica limitata alla cultura del videogioco, separata/segregata dal Mondo dell'Arte, ivi inteso in senso beckeriano?

Isabelle Arvers: Il machinima può stimolare le nostre menti e veicolare differenti messaggi. Ridefinisce le nostre capacità percettive e ci costringe a prendere le distanze dai videogiochi commerciali. C'è una lunga tradizione nella storia dell'arte che prevede l'incorporazione di giocattoli e pratiche ludiche all'interno dei processi artistici. Il machinima è semplicemente l'ultima iterazione di un processo che ha tra i suoi pionieri movimenti d'avanguardia come il DaDa e il Surrealismo. Per entrambi questi movimenti, l'intrattenimento e il gioco erano le forme d'arte più sovversive. Per loro, il gesto ludico poteva diventare un potente strumento critico.

I videogiochi e il Surrealismo presentano più affinità di quanto si possa credere. Si pensi, per esempio, al fenomeno dei sogni videoludici, ovvero la tendenza a visualizzare sequenze di un videogioco o la risoluzione di un rompicapo particolarmente difficile durante il sonno... Non ci sono dubbi che i videogiochi influenzano la nostre psiche, forse a livello inconscio. Produrre un machinima significa riconfigurare il mondo di un videogioco, il comportamento dei personaggi che lo abitano, le caratteristiche di uno scenario o degli oggetti ivi contenuti. Il creatore di machinima cambia il colore del cielo, modifica la velocità di animazione o altera le variabili di gioco. Come qualsiasi altra forma d'arte, il machinima influenza il modo in cui percepiamo la realtà. Si consideri il celebre saggio di Oscar Wilde, "Decadenza della menzogna”: tutte le idee che lo scritto ha espresso allora sono ancora valide. Non credo che il machinima sia una mera espressione della cultura videoludica. Non è separato dal Mondo dell'Arte e certamente non segregato.

Quando il machinima non è esibito online o in un festival cinematografico ma nel contesto di un'esibizione d'arte, il machinima è presentato nella maggior parte dei casi come videoarte. Ma il machinima si presenta più come una tecnica che un genere in se stesso. Spesso, quando gli spettatori vedono il machinima in uno spazio artistico e non hanno grande dimestichezza con i videogiochi, non sono in grado di riconoscere il testo sorgente, ovvero i videogiochi. Tutto quello che vedono sono immagini tridimensionali sullo schermo. Computer grafica. Tuttavia, questo non riduce il valore dell'opera né compromette le capacità degli spettatori di comprendere ed apprezzare ciò che vedono. Inoltre, dato che il machinima è tutt'ora considerato un "nuovo genere" dopo vent'anni di esistenza, gli artisti che lo utilizzano sperimentano e prendono in prestito aspetti del linguaggio cinematografico o della videoarte. Oggi, poche opere machinima sono così influenzate dal videogioco da risultare incomprensibili per un'utenza completamente a digiuno di cultura videoludica. Ritengo tuttavia che il machinima debba diversificare la propria estetica e interagire con differenti discipline al fine di diventare qualcos'altro, qualcosa di più, per esempio, diventando uno spazio abitabile anziché mere immagini su uno schermo.

Isabelle Arvers, machinima, #labRes2015. Cfr. http:// ruralscapes.net/isabelle-arvers/