Hugo Arcier (Photo courtesy of Hugo Arcier)

HUGO ARCIER: "WE ARE LIVING IN A SIMULATION"

In this interview, French artist Hugo Arcier extols the joys of virtual hiking, explains why game playing is usually a “passive” activity, and what it really means to be stuck in limbo.

Hugo Arcier is a French digital artist - or, rather, “an artist in a digital world” - who uses 3D computer graphics to create videos, prints, and sculptures. Initially interested in the field of special effects for feature films, he worked on several projects with Roman Polanski, Alain Resnais, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet. This practice has allowed him to gain a deep understanding of digital tools, in particular 3D graphic images. His artistic works have been exhibited at international festivals (Elektra, Videoformes, Némo), galleries (Magda Danysz, Plateforme Paris, etc.), art venues (New Museum, New Media Art Center of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Le Cube, Okayama Art Center, Palais de Tokyo, etc.), and several contemporary art fairs (Slick, Variation).

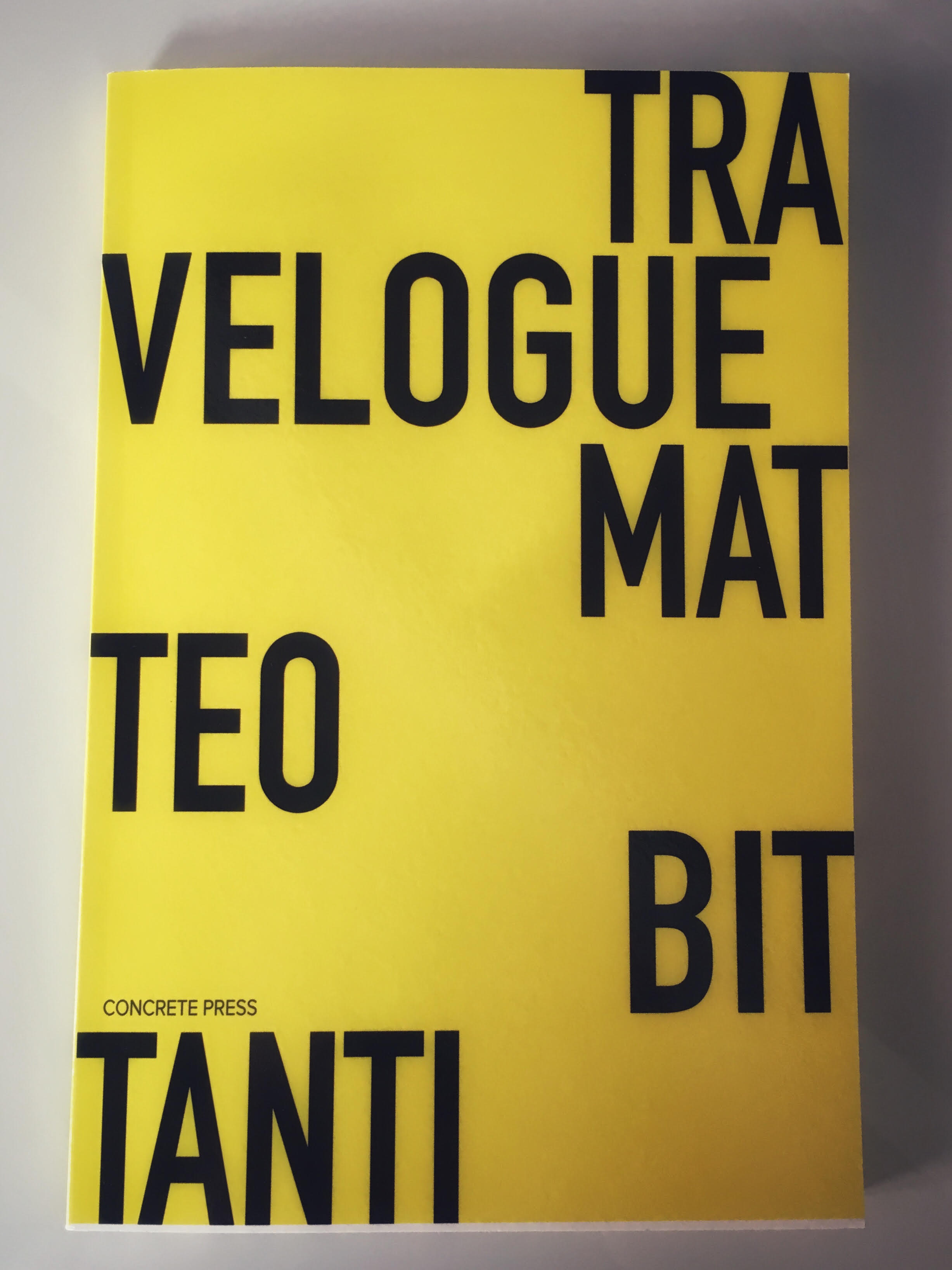

Arcier's LIMBUS (GTAV) (2015) is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Hugo Arcier, Ghost City, 2016

"A video installation by Hugo Arcier with an original music by Bernard Szajner Draws on De rerum natura of Lucrece, the installation Ghost City is built around a reinterpretation of the set of the famous game GTA V. The spectator is plunged into an environment without any population. The focus is put on architectural and graphic elements. It is a meditative and captivating experience. This virtual universe solicits both the present (the experience of the artwork) and the memory. This installation will be visible first at my solo exhibition "Fantômes numériques" at Lux Scène Nationale. "

Matteo Bittanti: One question I ask all the artists involved in TRAVELOGUE is to describe their personal relationship to simulated and real driving, that is, to video games and cars (= “concrete”, metal-and-plastic automobiles). According to Marshall McLuhan and Charissa Terranova, as a bodily extension or prosthetic, every technology - including cars and digital games - simultaneously augments” and "amputates" human beings. How do you address this tension in your work?

Hugo Arcier: In regard to my personal relationship to video games, I have to confess I consider myself a hardcore gamer. In fact, I play games nearly every day. My passion for gaming goes back to the 1980s. I discovered video games on my cousin’s Amstrad CPC. It was a true revelation. I started with adventure games, then moved onto beat’em ups and platforms. I begged my parents to purchase me this machine, but when we went to the store, the seller was adamant about PCs. This new platform was relatively new at the time and more powerful. So we bought a personal computer, but I was disappointed because the graphics were not as good as on the Amstrad. But things changed, as you know. Home computers eventually disappeared, while PCs became the ideal gaming platform. I have been a PC gamer since then. What fascinates me most about games is their environments. Games are a spatial medium: this is why I am particularly attracted to open worlds: there is nothing I like more than exploring digital places. I am also attracted to first-person shooters. I consider myself a virtual hiker. To me, playing a games means to explore, to take photographs - screenshots - and to scrutinize everything that I encounter. When I play, I eventually abandon the main, imposed narrative to go off on a tangent. I do not own a car since I live in Paris. Paris does not like cars at all: the traffic is insane and parking is nearly impossible. I use my bike and public transportation to go pretty much everywhere. And let’s face it: combustion cars are a relic of the past. They are noisy and cause massive air pollution. Their main byproduct is smog, which in turn causes lung cancer and other health related issues. All that cars produce is detrimental to human beings. Recently I saw a short documentary from the INA archive that discusses an electric car invented by a French engineer called the electric egg. It was available in 1942. I found this document utterly fascinating: it somebody were to launch such a model today, it would be as futuristic and modern as it was back then. I cannot understand how and why combustion cars have lasted so long. It is as if we were still using the Amstrad today: a complete anachronism.

Séquence Renaissance, 2012. Lighting/rendering of the sequence by Hugo Arcier.

My approach to virtual cars in gaming and 3D animation is very different. These cars exist in a space where they cause no health issues to humans. I love simulated driving: it is a form of pure escapism, devoid of any “real” consequence. I do not fetishize cars per se. When I play a game I am more attracted to arcade driving styles, which emphasize spectacle over verisimilitude. There is something truly hypnotic in virtual driving. Technology has positive and negative consequences, but - all things considered - I disagree with McLuhan that it “amputates” human beings. Technology has mostly positive side effects. It does expand human capabilities considerably. I do not have any faith in organized religions. I am extremely skeptical on anything that evokes the notion of the supernatural. At the same time, I am fascinated by the idea of a technologically enhanced life. Concepts like transhumanism have a certain appeal to me. I admit that my optimism is a weakness of mine. I do recognize that technology is akin to a secular religion. What truly concerns me, in the long term, is that technology can make human beings lazy, complacent, and thus less intelligent. Their technological aids can become like crutches. We increasingly use highly sophisticated devices and we have no idea how they are produced. Artists are a particular kind of user: they want to know how things are done. Artists must show what lies underneath the surface of particular technology. This is why I developed projects like the Limbus series: to show games from an unusual perspective, to disintegrate the alleged realism of virtual worlds. My recent installation, Ghost City, is about the fact that virtual worlds are shallow universes, literally, like empty shells.

Hugo Arcier, Limbus (Rage), 2011

"Sometimes a bug in a video game can be magic. It gives the keys to a normally unexplored area, beyond, in the limbo of the game.

Parfois, un bug dans un jeu vidéo peut être magique. Il donne les clefs d’une zone en marge, normalement inexplorée, située au-delà, dans les limbes du jeu." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: In the TRAVELOGUE exhibition, we showed LIMBUS (GTA V) (2015), the follow up to LIMBUS (RAGE) (2011). These two works exemplify the difference between "found" and "enacted" glitches. What does the glitch represent to you? A fragment of the technological unconscious, a symptom of the true nature of simulation, a purely aesthetic style or something else altogether? And what is the "limbo of the game" you mention?

Hugo Arcier: Video game glitches are very important because they grant the user access to something that is usually inaccessible, something users are generally not allowed to see. Thus, glitches produce a powerful distancing effect: the player is abruptly reminded that each simulation is an artifice, a conceit, and a deception. Although gamers are usually considered “active” in their interaction, they are mostly passive. The glitch awakens the player from her torpor: suddenly the player realizes that the ultra-realistic world she is immersed is a “just a game”. This distancing effect - almost like an epiphany - is relatively uncommon in other media. In movies, this effect can be encountered only in auteur (think Jean-Luc Godard) or amateurish productions (Z-movies and the likes), but in video games, this phenomenon happens even in triple AAA productions, the equivalent of a highly polished Hollywood blockbuster. To create the Limbus series, I specifically looked for a point of view outside the level of the game. I took advantage of a technical optimization technique of video game production: every polygon is single sided, so if you see something from the wrong angle it becomes transparent. This conundrum leads to something visually fascinating. If you can see the level from below, the ground completely disappears, but the characters and props behave as if nothing happened. I have discovered this glitch completely by chance and I captured it to create the first Limbus, in 2011. The process entailed a documentation of the glitch encountered in the video game Rage via screen capture. I felt I had to save something that a subsequent patch might have erased forever. To create the second Limbus in Grand Theft Auto V, I intentionally used a cheat mode: I made myself invincible and I teleported myself to a specific area of the game. But the process was not necessarily easy. The cheat mode did not always worked well and the “perfect spot” was hard to find. In regard to your question about the “limbo” dimension of a game, to me it’s basically a place outside the game itself. But limbo has religious connotations as well. It is a synonym of purgatory: a place where the soul is temporarily “parked” after someone’s death. It’s an in-between area, a liminal space. The video game equivalent to me is when you reach a point where you cannot proceed in the story as if you were dead: you can only wander around and look in a sort of out-of-body experience. In short, to be stuck in limbo means to be waiting for something to happen in a grey zone, not hell, not paradise. Something else altogether.

Hugo Arcier, FPS, 2016

"An interactive installation by Hugo Arcier Music by Stéphane Rives and Frédéric Nogray (The Imaginary Soundscapes) FPS is a post November 2015 Paris attacks art piece. The artist deals with blindness hijacking video game codes, in particular of first person shooter game. The only visible elements are pyrotechnic effects, gunshots, muzzles flashes, sparks, impacts, smokes. All these elements reveal a decor and impersonal silhouettes, innocent persons denied by the subjectivity of the character we incarnate. From dark to light, a blindness is replaced by another one. Gunshots after gunshots a memorial is created before our eyes.

FPS Installation interactive de Hugo Arcier Musique de Stéphane Rives et Frédéric Nogray (The Imaginary Soundscapes) FPS est une œuvre post-13 novembre 2015. L’artiste y traite du thème de l’aveuglement en détournant les codes du jeu vidéo, en particulier du jeu de tir à la première personne (first person shooter). Ne sont visibles dans l’œuvre que les effets pyrotechniques, coups de feu, traînées, étincelles, impacts, fumées. Tous ces éléments révèlent en creux un décor et surtout des silhouettes impersonnelles, personnages innocents niés par la subjectivité du personnage que l’on incarne. Du noir à la lumière, un aveuglement en chasse un autre. Coup de feu après coup de feu se crée sous nos yeux un mémorial." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: The notion of simulation occupies a central position within your practice. Your work brings to the surface the ideologies of digital technologies that we usually take for granted, from first-person shooters to action games, from computer animation to machine learning. How do you approach these issues as an artist, that is, as opposed to a scholar who is interested in using words and concepts to illuminate a process or a documentary filmmaker whose main goal is to document a situation via an edited audiovisual recording? How do you grasp and communicate the essence of computer graphics and algorithmic worlds through your artistic practice?

Hugo Arcier: An artist focuses on the same subjects that may fascinate a scholar or a filmmaker, but with a less theoretically-oriented approach. Art is not about explaining something. Art is about addressing the sensible. Here, the emotional and the experiential always come first. They may lead to reflection - which in turn leads to enlightenment - but only at a later stage. My artistic practice focuses mainly on computer graphics. As you know, the video game is just one of the many artifacts using computer graphics. I try to capture its essence by applying different strategies. First of all, I operate through a process of dissection: I remove layers of data until I can show one single, bare element in each series. In a sense, my modus operandi is similar to an autopsy: this is how one learns about anatomy. You start from a very complex, opaque, difficult to understand whole - a body - and then you start to take it apart, cutting smaller sections. Secondly, my goal is to make computer graphics and algorithms visible, legible, and recognizable. In fact, these elements tend to be generally invisible, under-the-hood so to speak. Even in my more realistic projects like the film Nostalgia for Nature, the simulation is rendered visible. This was meant as a meta-discourse on computer graphics, in a self-reflexive manner, a film-within-a-film.

Hugo Arcier, Nostalgia for Nature, 2012.

A co-production Hugo Arcier and Le Cube Music of Cocoon, “Paint it Black” (Optical Sound) Voice over written and said by Agnès Gayraud English translation by Dylan Joseph Montanari Spanish translation by Open This End (OTE), Guillermo Remón Garcia.

Nostalgia for Nature is a true sensory experience, a film composed entirely of computer-generated images. It immerses us in the spirit of its protagonist, an ordinary city dweller who recollects moments and scenes from his childhood, all inextricably tied to nature. Guided and accompanied by off-screen narration, these flashbacks intermingle, diffracted by his memory. The film, however, rejects Manichaeism, revealing nature as far from idyllic…rather, as somber, at times ominous, but always fascinating and beautiful. The paradox of representing nature through computer-generated imagery lies at the heart of the film. It is also where its nostalgia resides. The film is a declaration of love to the incredible forms engendered by nature that we no longer see or, rather, no longer know how to see.

Nostalgia for Nature est un film sensoriel entièrement réalisé en images de synthèse. Il nous plonge dans l’esprit d’un personnage citadin qui se remémore des moments de son enfance liés à la nature. Guidés par une voix off, ces flashbacks s’entremêlent, diffractés par sa mémoire. Le film n’est pas manichéen, il montre une nature – loin d’être idyllique – sombre, parfois inquiétante, mais fascinante et belle. Le paradoxe de représenter la nature par des images de synthèse est au cœur du film. C’est aussi là que se situe la nostalgie, et le film est une déclaration d’amour aux formes incroyables engendrées par la nature et que l’on ne voit plus ou que l’on ne sait plus voir." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: Terms that "ghosts", "nostalgia", and "disappearance" recur in your works. Does simulation replace reality, as Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio argued? Or is simulation just another layer, another mode of being? And why is it so important for you to document this phenomenon through your artistic work?

Hugo Arcier: These notions - disappearance, substitution and more - are absolutely central in my work. I don’t know exactly what qualifies as “reality” any longer and probably I don’t care because what is important is what you experience, what you see, what you hear, and - at a deeper level - the information stored in your brain. From this vantage point, we can say that simulation replaces reality. Simulation has already won the battle because it is more malleable, efficient, flexible. You can’t take any risk in real life: people don’t like that. They like “safe”. Many years ago, I was commissioned a project to make a very realistic tree in computer graphics. That did not make much sense to me: so I asked “Why don’t you just shoot a real tree with a camera?”. They responded, somehow annoyed, that it is cheaper to make a tree in computer graphic that paying a filmmaker and a professional crew to film it. Plus, you need to spend time finding the perfect tree with all the leaves in the right spot, a certain kind of trunk… The shooting may be compromised by real-life situations like unpredictable weather conditions (rain, wind, low light etc.). In short, they said, a simulated tree is better than a real tree. When I heard this explanation, I was shocked. I realized I just witnessed a turning point. As an artist, I chose to work with the medium of computer graphics because that puts me in the trenches, in the frontline of the contemporary. To me, it’s essential to document the transformation of our world into a massive simulation and to accomplish such goal there is no better tool available than the simulation itself.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman

JEAN-BAPTISTE WEJMAN: "VIDEO GAMES ARE RAW MATERIAL THAT ARTISTS CAN - AND SHOULD - EXPLOIT"

In this interview, French artist Jean-Baptiste Wejman explains why Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe's works are "game-like" and why simulations and fictions are deeply intertwined.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman is an artist living and working in Toulouse, France. He received a Master of Arts in Fine Arts at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Bourges in 2014. An amateur photographer in his teenage years, he decided to become an artist at the age of 17, after attending a solo show by Mircea Cantor at FRAC in Reims. Influenced by artists such as Ryan Gander, Philippe Parreno, Pierre Huyghe, Cory Arcangel, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and Wolfgang Tillmans, he is interested in developing new practices of art and thinks that lacking a definition of art is, in itself, the most powerful engine for conceptual aesthetic thinking. His work has been exhibited internationally, including 35h (2015), a group show in Champigny-Sur-Marne near Paris, The Graduals (2012) at Traffic Arts Center in Dubai, and 43/77 (2009) in Bourges.

Wejman's installation Concentration Before a Burnout Scene is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you briefly describe your education and upbringing?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: I was lucky enough to experience an ordinary childhood, like many other kids growing up in the Nineties in France. As a teenager, I never envisioned that one day I would become an artist. I spent the best years of my youth playing video games, riding my BMX bike, reading and collecting used books, and listening to as many audio cassettes as I could. When I was still young, I had the chance to try my hand at photography with an old camera. I discovered Art in school, between the age of 11 and 15. I have to express my gratitude to the French educational system: it made me realize that art was an exciting field, not a moribund, boring discipline. I chose to concentrate in Fine Arts during my high school years. Around that time, I visited my first exhibition of Contemporary Art and that event changed my life. I had the opportunity to take excellent courses in Art History and I developed my first projects. Today, I keep them hidden in a remote space of my parents's garage! Back then, I enrolled in several science-based courses, but my passion for art was too strong to resist. Luckily, I was accepted by L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts in Bourges. Those were intense times. This is when I began to focus on a set of artistic concerns and to fully develop my art practice. I was very interested in research: I began investigating the status of the image, the deep meaning of photography, what lies behind the surface. My interest was definitely conceptual. In school, I kept asking myself: "What is my role as an artist?", "What is the goal of making art, today?", "What's the point in creating yet another image in the Twenty-first century?", "What kind of exposure can an artist's project receive?" and many more questions like these. Meeting like-minded peers was essential. Students, teachers, assistants, fellow artists... The conversations were intense! L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts gave me the chance to immerse myself in a lively art milieu and to participate in engaging discussions, stimulating debates, and constructive critiques. Finally, in 2014 I received a Master of Arts with honors. Since then, I have been developing my artistic activity.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Reprise, reprise déprise, 2016

Matteo Bittanti: Why did you begin to incorporate video games in your practice? What do you find fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality? Or are you more interested about the online communities that blossom around digital games?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: These are all excellent questions. Why? Well, for a long time I thought that the boundaries separating Art from "everything else" were clear, rigid, and somehow inviolable. Universal laws, so to speak. However, as time went by, I was forced to rethink my assumptions and to question my own prejudices. I was influenced by several critics and thinkers. One is Paul Ardenne, who believes that art should always be contextualized. He says that we must abandon the notion that each artwork is an autonomous object, existing in a vacuum. Ditto for Hal Foster, whose emphasis on theatricality forces us to think about artistic situations as always spatially situated. Since the Nineties, these discussions have evolved considerably: they might have taken new forms, but they certainly have not ended. Initially, what fascinated me about the role of video games within the contemporary visualscape was the ongoing debate around their status as art. As you know, "Are video games art?" is a question that dominated the conversation in the late Nineties and early Zeroes. For several critics, video games are just commercial artifacts, the byproduct of a creative industry akin to Hollywood. Other believe that games are still in their infancy, and, as such they are "under underdeveloped": once artists and intellectuals start unpacking their true potential, they will evolve in unexpected ways, subverting the conventions and clichés of mainstream productions. I began incorporating games in my practice around 2011 when I recognized their cultural value. To me, they were raw material that could - and should - be exploited by artists. Today, it is obvious to me that digital games are just another way of making art. We are overwhelmed by a staggering production of fiction, images, and interactions. We now posses the technical means to navigate virtual spaces. In a sense, we made Leon Battista Alberti's dream finally happen. My generation grew up watching a world unfold not outside "windows" but on Windows, jumping from one tab to another, playing with all sorts of information, assuming different identities and characters. As an artist, I wanted to partake this conversation and to experiment with new media. When I incorporated games in my artistic practice, the process felt natural, almost automatic. Perhaps even necessary.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Une table modifiée pour une machine qui génère un monde qui génère un personnage qui génère un voyage, 2014

Matteo Bittanti: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for their users. How do you relates to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension throughout your work in general and specifically in Concentration Before a Burnout Scene?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: The complex relationship between reality and simulation? This is where all the traditional questions of art clash and collide! Making pictures, chasing mimesis, imitating the real... And this is the reason why video games are so exciting. They force us to confront, once again, the notion of realism. And yet, we must not forget that since the early days of game development, many designers rejected realism in toto, offering instead alternative, more abstract, oneiric experiences. They questioned the notion of aesthetics in art through an image-based form of production. I must also add that, to me, the concept of simulation is closer to the broader concept of fiction. Not only these two notions have strong ties, but they inform each other, they are mutually reinforcing. In my practice, fictions act as simulations. For example, my video Concentration Before A Burnout Scene can be read on several levels. Initially I chose GTA San Andreas because I was fascinated by the very idea of the open world. This is where simulation truly matters. I produced this video by recording my own experience - mediated by an avatar - within the game world. This project qualifies as a machinima. At the same time, I selected a specific context and time frame within the game to extract some elements and to perform a loop. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene depicts the game in a static moment. It is a false movement stuck in an infinite time loop. In short, I simulated play time. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene is not about the "real" game, changing, developing and transforming before our own eyes. It is, on the contrary, a dramatization which offers the viewer the chance to experience an alternative experience of time. A simulated time that produces a duration in the so-called real world.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Live Wire Introduction, 2014